When the Earth Remembers

Bones of the Plains: A Spiral of Memory

An Indigenous Perspective Public Artwork in Oklahoma City

Once more they scatter us from the earth where our mothers’ spirits dwell. Beneath waning skies, we clutch at fading embers of our home, hearts heavy with the memory of roots torn free. Yet even as strangers on parallel earth and the facsimile stars, the quiet echoes of our ancestors stir courage in our steps. A whisper we cannot ignore, Grandmother, rising like dawn, calling us towards the hearth of recollection and light.

How and Where do we even Start? ---- Being drawn to telling stories through figurative narratives—stories about culture, history in the now, and about strength. Thinking about a public artwork for Oklahoma City, in a place brimming with so many different Indigenous Nations, cultures, and people harmed by removal and land grabs, it’s impossible not to return to the concept of “home” and how easily it was stripped away. So many of us talk about displacement like a statistic, or as ordained by will from a higher authority. There has to be a baseline, core concepts and ideas: the displacement of home, the extortion of environment and habits of nature, the commodity of owning everything one can see, the lack of synergy with living world.

Starting with figurative pieces. It’s how I learned to express the breadth of human experience. There’s so much potential in portraying the deep culture behind the stories rather than the majority stereotypical “male warrior” figure we see too often. We have an entire universe of narratives from Southeastern Woodlands traditions, Plains traditions, and Mississippian influences—each with a vibrant tapestry of characters and symbolic forms that can be illuminated. For instance, my Human Head Effigy Pots grew out of that desire to carry-forward Mississippian artistry. I’ve imagined these effigy vessels—contemporary expressions of masterful forms—finding a place in a public setting. But this is from a deeply personal desire and work that I would love to create at the right time and space within public forum.

It becomes clear that any meaningful approach must center on the land, an approach that speaks directly to the soil itself. Because the displacement isn’t just about people—it is about the severing of land from living cultures—it is the breaking of bonds between living cultures and the earth they exist in. Looking at this massive puzzle—thirty-nine different Nations, each with unique histories and knowledge systems—there is a deep prelueding question: How can the artwork represent so many voices without collapsing them into some watered- down concept? The last thing needed is a cliché that pretends to stand for everyone.

When a home is lost, what remains? And how does that absence affect the fabric of a community? What would be the symbol of a home as its conceptual interpretation— perhaps a literal house? Housing, that provides safe spaces, shelter, comfort, rest, and healing. If the house is a symbol of “home,” then flipping the house upside down and burying it in the earth--potentially this could represent the absences, the removal of “home.”

Then there are the realities of location constraints near the Bricktown River Walk Park and a budget that wouldn’t allow for something towering in stature. Shifting to a land-based approach—literally removing earth, digging into the ground. Because the Land Run Monument is a narrative about expansion, pushing forward, and claiming “open space,” I wanted to invert that process. Instead of building upward, I’d go downward, turning the physical act of land removal into the statement.

Imagining this rectangular foundation—an allotment, oriented toward the east or the river—an actual “foundation” as if for a house, but excavated so visitors would step down into it. The question was how to shape it so it felt meaningful and not just a hole in the ground. For me, the concept of a “house” is symbolic of home, security, belonging—so by burying it, or inverting it, I could signal the loss and disruption inflicted on Indigenous families. Looking at localized architecture structures, the geometry of a Wichita Grass House could hold that symbol and message. The conical, dome-like shapes speak volumes about how local-living communities built their homes in harmony with local materials. Reversing that shape and sinking it into the earth evokes upheaval, intrusion, and disconnection. Filling this secondary voluminous hole with cast bison bones. A community endeavored to cast and create the bones from molds, invoking the extreme loss of the populations of bison that were vital for the environment. Yet, it can also become a sort of ceremonial chamber—somewhere to gather and reflect. Perhaps too large and too ambitious - to create a large-scale land art that can dual as a meeting site for Native Communties.

Yet, in turning to the earth, in physically engaging the land, we create a new narrative—one anchored in communal making (those cast bones) and spatial dialogue for visitors to understand the deeper conversation and story that is linked to the land run monument. We need a living space where the land, the people, and the memory of wildlife and culture are all braided together. Feet pressed to the ground in dance, counterclockwise, spiraling as the story keeps being told and a grounded statement on resilience and re-connection. “When the Earth Remembers: Bones of the Plains: A Spiral of Memory”

“When the Earth Remembers” is a site-specific installation in Oklahoma City designed to challenge the one-sided narrative of the Land Run Monument. Using cast concrete bison bones and bronze bison skulls arranged in a counterclockwise spiral, the artwork re-centers Indigenous perspectives by symbolizing the removal of lands and cultural resilience. By connecting the artwork with the land, visitors experience a reinterpretation of history that honors the significance of our homes, environmental balances, community collaboration, and the sovereign voices of Native Indigenous Nations.

Conceptual Background

Emerging from the desire to acknowledge the ongoing impact of the Land Run on Indigenous nations—between nations of the plains and woodlands—whose ancestral and federally assigned lands were systematically opened to non-Native settlement through legislative acts (Homestead Act, Curtis Act) and culminating events like the 1889 Land Run. Drawing on scholarship by Angie Debo (And Still the Waters Run) and Vine Deloria Jr. (American Indian Policy in the Twentieth Century), the project foregrounds Native experiences of dispossession and survival.

The spiral itself, a counterclockwise form, references our stomp dance and speaks to reversing or re-examining the celebratory pioneer narrative. While the Land Run Monument dramatically conveys the settler rush for “free” land, the artwork symbolically lays bare the cost of that expansion: dismantled nations’ sovereignty, the near-eradication of bison, and fractured ecosystems. By employing bison bones—long iconic of Plains life and spiritual practice—the artwork honors the memory of a keystone species integral to Indigenous subsistence and culture.

The piece also reflects Southeastern Woodlands traditions that many relocated nations adapted to life in Indian Territory—referencing cyclical, spiral-based cosmologies seen in mound sites or Mississippian iconography, and bridging Plains and Southeastern identities that converge in today’s Oklahoma.

Site-Specific Relevance

Oklahoma City’s Bricktown Canal and the Land Run Monument form an environment saturated with pioneer iconography, yet needed counter-conversation and additional contextual storytelling from the perspectives of Indigenous Nations. Installing the artwork in proximity to that site provides a powerful counterpoint: a place where visitors can confront the absent narratives of forced removals, broken treaties, and ecological upheaval. It becomes a touchstone for dialogue about community healing, historical truth, and the path toward reconciliation.

Practical Access: The proposed location is publicly visible and walkable, linking modern urban life with the city’s layered past. The adjacency to the river (Bricktown Canal) underscores bison’s historic reliance on water sources while symbolically inviting reflection on the environmental impact of rapid colonization.

Community & Cultural Connection

Central to this artwork is community participation. The cast bison bones can be produced through collaborative workshops hosted at local Native cultural centers—inviting Native members and other residents to physically shape the sculptures in concrete. This process ensures the project isn’t just about representation but also about co-creation, honoring living Indigenous voices.

For educational and cultural gatherings, the spiral’s location can become an informal “meeting circle” for ceremony, discussion, or prayer—mirroring the communal spaces many Native traditionally built at the heart of their villages or mound complexes. Ultimately, providing a platform for continued storytelling: bridging historical research, artistic expression, and contemporary Indigenous experiences.

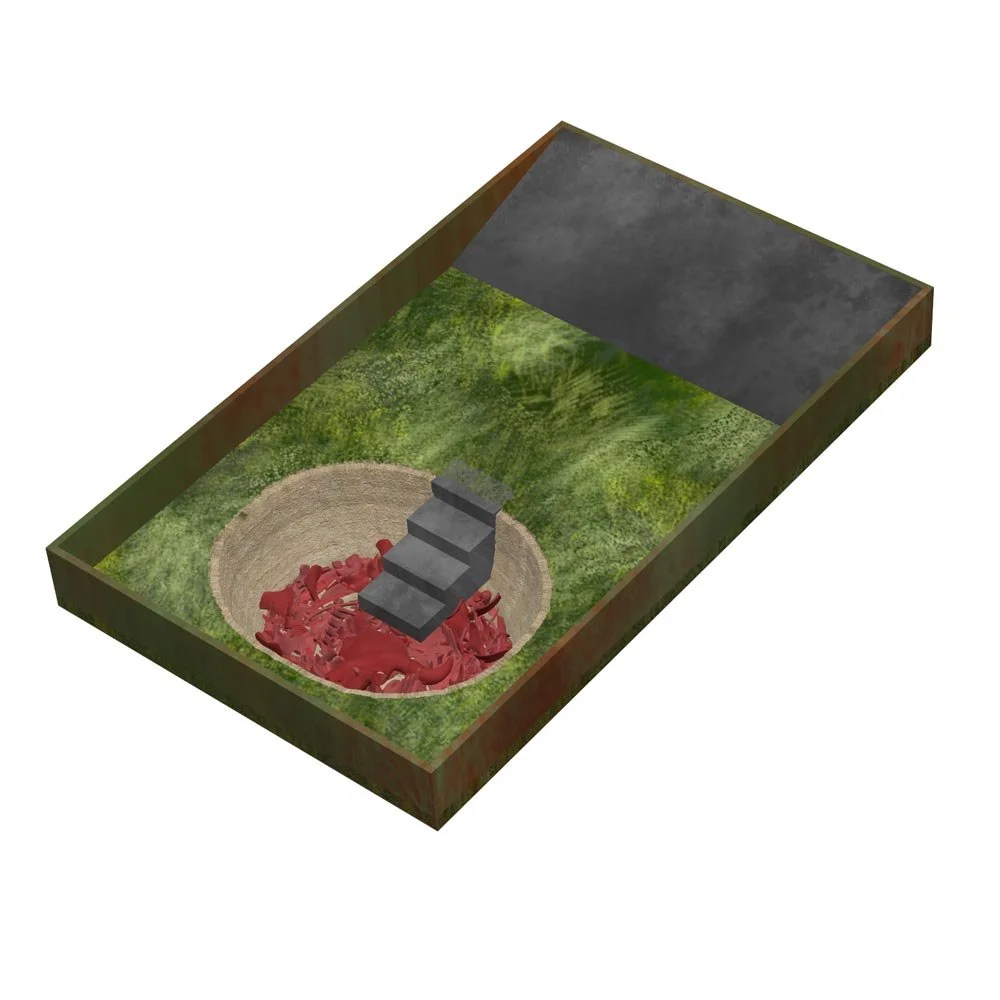

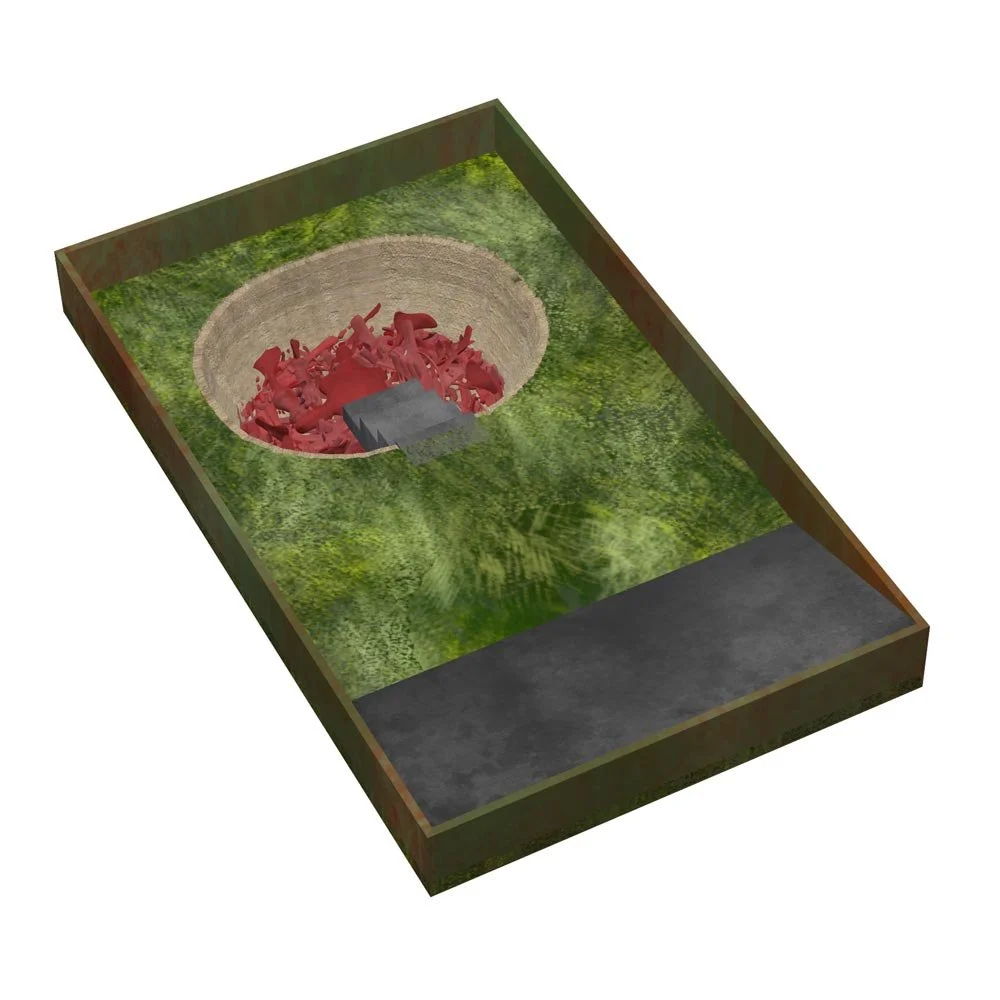

Rendering for Concept and Illustration Purposes.

Visual Design + Materials + Fabrication

Description of Visual Form

Visitors’ first notice approximately 100-feet linear spiral, with a total diameter of 18-feet laid out on the ground, winding outward in four counterclockwise rings from a central bronze bison skull. The line that draws this spiral is formed by cast concrete bison bones, approximately 1–2 feet each in length, placed end-to-end (or slightly overlapping) to create a distinct “road.” At the outer edge, a second bronze skull anchors the piece, visually marking both an end and a new beginning in the spiral’s cyclical design. From above, the shape resembles a labyrinth or geoglyph, quietly inviting people to enter and reflect.

Materials & Finish:

Concrete Bison Bones

High-strength, air-entrained concrete with integral coloring (a warm red hue) ensures freeze-thaw durability suitable for Oklahoma’s climate.

An internal wire mesh or rebar armature is embedded in each bone to provide structural integrity.

Bronze Skull Casts

Each skull is meticulously sculpted from real bison references, molded in silicone, and then cast in bronze at Two Ravens Studio, where I contribute to the craftsmanship. This process guarantees longevity and creates a visual contrast against the concrete backdrop.

Surface Treatment

A breathable concrete sealer will be applied to protect the cast bones from moisture infiltration, enhancing durability.

The bronze will be treated with my signature patina, which brings an element of nostalgia by resembling Turquoise Stone, a personal homage to my Grandfather and our shared experiences in Arizona.

Fabrication & Installation:

Mold-Making & Casting

Silicone rubber molds will be created for approximately eight bone types, along with a bison skull. Community workshops will enable participants to cast using red concrete, embedding reinforcement wire to mitigate the risk of cracks. Once the concrete has cured, the bones will be demolded and sealed for durability.

Site Preparation

The selected site will be approximately 18-feet in diameter to ensure ample clearance. The area will be lightly leveled, and native plants will be incorporated for landscaping to enhance aesthetics and create a natural boundary. The bones and skulls can be either surface-laid or partially embedded in a shallow trench for added stability. Beneath the concrete pieces, drainage gravel will be used to prevent water pooling.

Maintenance & Durability

The concrete components are specifically designed to withstand long-term outdoor conditions. The bronze skulls may require periodic waxing or a protective coating; however, they are generally resilient to weathering effects.

Rendering for Concept and Illustration Purposes.

Public Engagement & Community Impact:

The sculptural installation serves as an interactive medium for storytelling that transcends traditional forms of art. By engaging local Native community members and Oklahoma City residents in the hands-on process of casting, the artwork creates a dynamic narrative that reflects both resilience and introspection. Through workshops, participants not only gain insight into historical injustices such as the Land Runs and forced land allotment but also celebrate contemporary Indigenous artistry and community cohesion.

Situated near the Land Run Monument, the installation prompts critical conversations about which narratives are prioritized and how society reconciles the glorification of pioneering history with the complexities of dispossession and trauma. The spiral design of the piece naturally encourages visitors to explore, pause, and engage, making it an ideal venue for pop-up educational programs and cultural gatherings within its circular space. Thus, this installation not only enhances public engagement but also nurtures a continuous dialogue about the intricate history that shapes the identity of the city. Each visitor is invited to contemplate and contribute to the evolving story of Oklahoma City’s diverse heritage.

Timeline Overview:

1. Design & Final Approvals (Weeks 1–4)

Finalize site permissions, budget, and collaborative workshop schedule.

2. Mold-Making & Prototype Casting (Weeks 5–10)

Sculpt master bone forms, produce silicone molds, test a few cast samples.

3. Community Casting Workshops (Weeks 11–14)

Engage cultural centers, local schools, or arts organizations.

Pour and cure each bison bone in small batches.

4. Bronze Skull Foundry Process (Weeks 5–14, concurrent)

Sculpt the bison skull, create foundry molds, pour and finish the bronze.

5. Site Prep & Installation (Weeks 15–18)

Clear/level ground, lay out spiral geometry, place bones and skulls.

6. Completion & Public Opening (Week 18+)

Optional dedication ceremony, media outreach, signage unveiling.

Call to Action: Collective Creation:

When the Earth Remembers is a public artwork currently in development for Oklahoma City’s Bricktown District. The installation—a spiral of cast bison bones and bronze skulls—creates a counter-narrative to the nearby Land Run Monument, inviting reflection on the stories of displacement, survival, and renewal that shaped this land.

At its core, the project is a collective act of remembrance. Each sculpted bone in the spiral will carry a carved design representing one of the Indigenous Nations currently in Oklahoma, creating a shared circle of memory and identity.

We invite participation from Native Nations/Tribes/Communities, Cultural Departments, and Artists/Creatives in three collaborative ways:

1. Cultural Representation

Contribute a line drawing or symbolic design from your Nation — a motif, figure, or visual story that can be incised into one of the sculpted bison bones. These carvings become permanent marks of presence and identity within the larger form.

2. Community Casting Workshops

In Spring 2026, Addison will host a series of Bone Casting Workshops across Oklahoma in collaboration with Native Cultural Centers. Community members will pour and cast the concrete bones that will be directly installed in the final sculpture — embedding shared authorship and collective memory into the artwork itself.

3. Ecological Collaboration

The installation site will be landscaped with native plants and materials guided by Indigenous ecological knowledge. We are seeking partnerships with Native horticulturalists, ethnobotanists, and plant knowledge keepers to shape this living environment and bring an Indigenous perspective to the land’s renewal.

This is an open call to the 39 Tribal Nations of Oklahoma to help shape this artwork through participation, design, and dialogue.

Together, we can create a space that speaks to both past and future — where the Earth remembers, and we listen.

Call-To-Action - Sign-Up-Form:

Open to—but not limited to (*please reach out for inclusion or corrections):

Native Nations and Jurisdictions in Oklahoma by Regions:

Eastern/Southeastern Oklahoma (The Five Tribes Jurisdiction): Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee (Creek), and Seminole Nations. Status: Historical reservations/jurisdictional areas affirmed as existing for federal jurisdiction (McGirt v. Oklahoma). Key Counties: Sequoyah, Cherokee, Adair, Muscogee, Tulsa, McCurtain, Bryan, Carter, and more.

Northeast Oklahoma (Peoria Area): Quapaw, Modoc, Wyandotte, Seneca-Cayuga, Ottawa, Miami, Peoria, and Eastern Shawnee Nations. Key Counties: Ottawa, Delaware, Craig.

Central/North Central Oklahoma: Osage, Kaw, Otoe-Missouria, Ponca, Tonkawa, Pawnee, Iowa, Citizen Potawatomi, Kickapoo, Sac and Fox, and Absentee Shawnee Nations. Key Counties: Osage, Kay, Noble, Pawnee, Lincoln, Pottawatomie, Oklahoma.

Southwestern Oklahoma: Comanche, Kiowa, Apache, Delaware Nation, Caddo Nation, Wichita and Affiliated Tribes, and Fort Sill Apache Tribe. Key Counties: Caddo, Comanche, Grady, Stephens.

Western Oklahoma: Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes. Key Counties: Custer, Roger Mills, Washita, and others.